In discussing Italian colonialism, I am always isolated when I try to differentiate the behaviour of Italian civilians and soldiers. I have difficulty making my point. However, history, only part of which is written, makes a clear distinction between civilians and military personnel in Africa. A striking example of this diversity was Ferdinando Martini, the first civilian governor of Eritrea (1896) after a series of military governors.

I would like to quote the following passage by Martini. It is reminiscent of the pen of a young editor of a left-wing newspaper. Honest words, heavy as stone, that reflect well on the writer and impel recognition not only by Italian historians but also by the people of the Horn of Africa, because Martini was on their side, as were most Italian civilians who lived and worked there.

“Were I not to speak my mind at the outset, you would never finish this book, which must be clear and honest about everything. We went to Africa without any clear motive; we wanted almost unanimously to remain, when it was time to come away while damage was still limited. Though I repeatedly and vainly asked that our soldiers be recalled from the coast of the Red Sea, I am now the first to confess that it is no longer possible to turn our backs on the Red Sea without dishonour. If policy changes with events and time, morality does not, and I cannot believe that there are two justices, one white and one black, two rights, one black and one white. In all humility I cannot understand how we were victims for centuries and now make victims of others. We are eclectic: we ask for the Isonzo and we annexe Mareb. When I point this out, people shrug: “Those are eighteenth century ideas”. Too bad about the nineteenth century! We are hypocrites: Degiacc Mesfin risked his life to free his father Ras Woldenkiel and his country from invaders. Were he born in the Roman Republic, we would put him down in history as an example of virtue towards homeland and family. Since he was born in Africa we lock him up in Santo Stefano prison. When I point out this contradiction, people sneer: “There is no comparison. We bring civilisation to Africa”. We are liars: it is untrue that we want to civilise Abyssinia. One does not need to live years in Africa like Schweinfurth to be convinced; two months is enough. These are not wild tribes that practise idolatry, but they have been Christians for centuries, with a political tradition of centuries. For centuries, conquerors and travellers have tried to impress traces of European civilisation but they will have none of it: their huts are those of biblical times and their present customs were known to Herodotus. We claim to wish to end the wars that make all human endeavour vain in those areas, but we continue to enlist and pay Abyssinians to kill other Abyssinians. Tell me that there are too many of us in Europe, whereas in Ethiopia there are only three or four persons per square kilometre, that colonies are necessary, but don’t tell me that we are bringing civilisation! Those who say that Ethiopia needs to be civilised either lie or are stupid.”

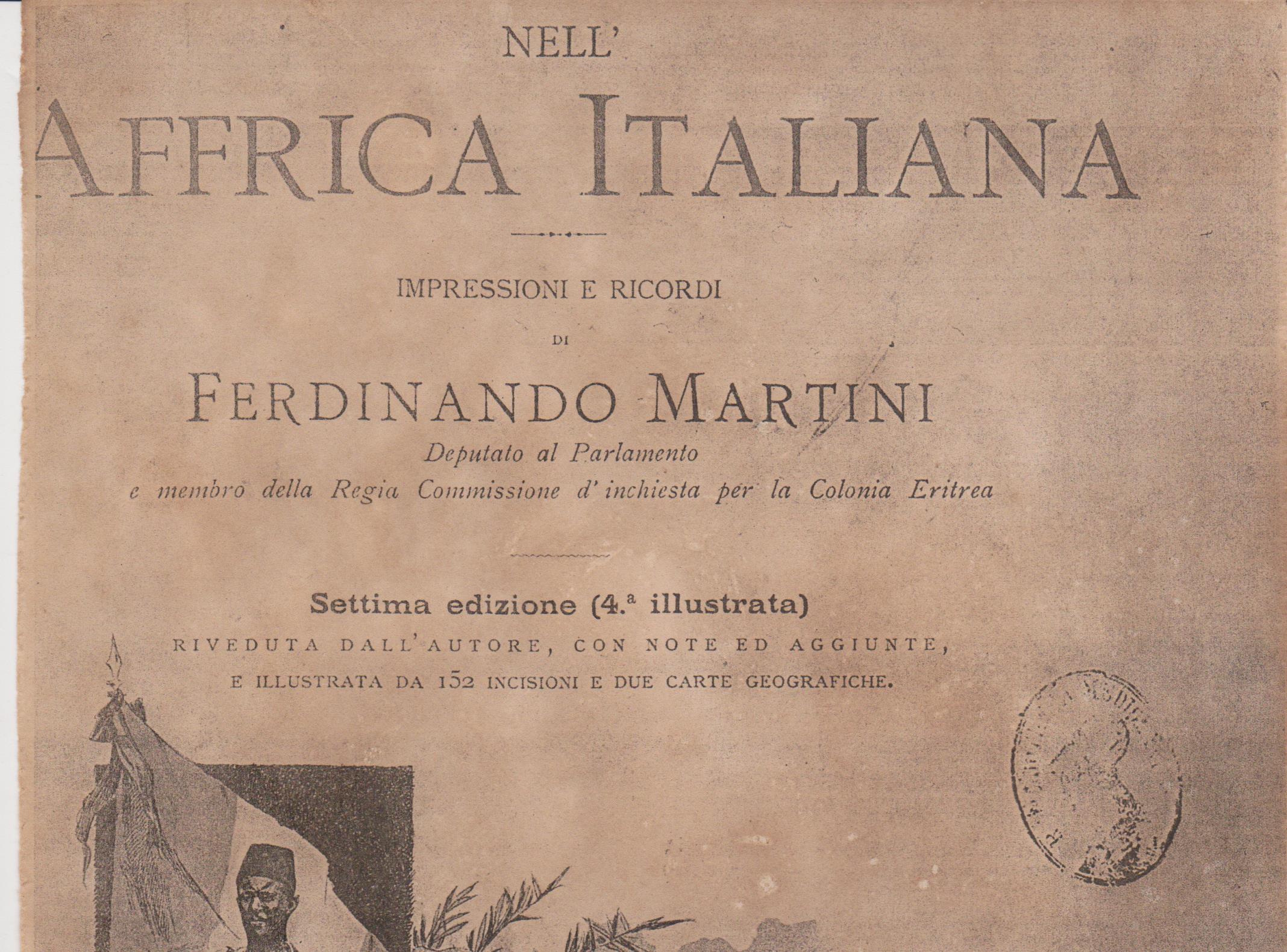

(from Ferdinando Martini: “Nell’Affrica Italiana”, Fratelli Treves Editori, Milano, 1896)