Valeria Isacchini

settembre 2015

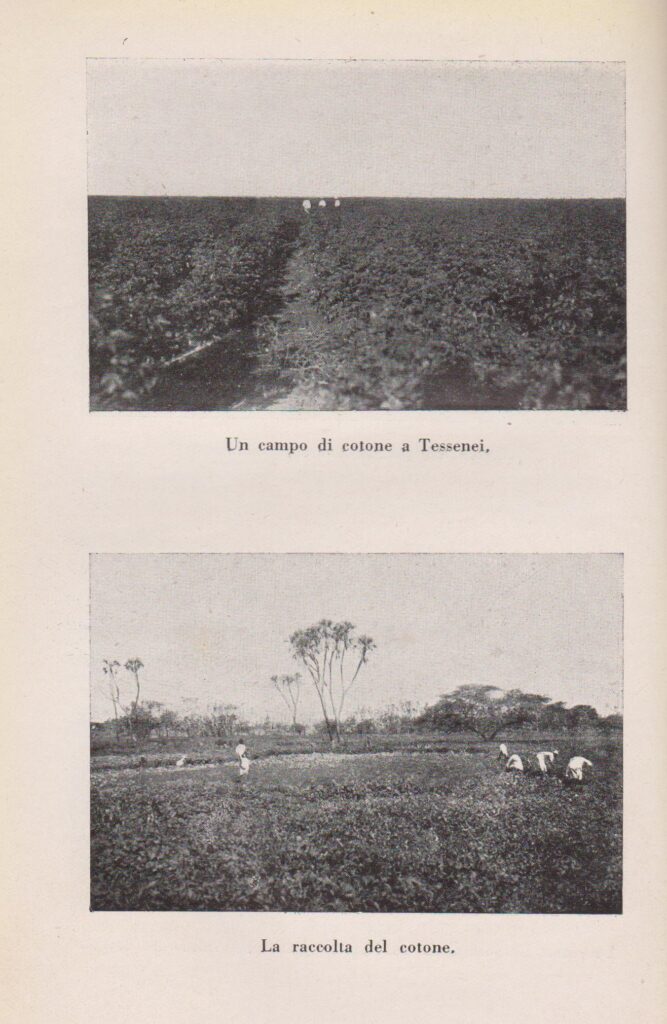

“About ten chilometers far, towards Abu Gamel –the Camel Mountain1–Alighidir, whose name sounds like an Arab tale, is a modern agricultural village, with comfortable brick cottages for the direction and the managers. Cotton and dura fields lie around, crossed by a wide net of channels; there, in the farms zone, several native families live…“So, in a long article, Giannino Marescalchi describes the beginning of the industrial cultivation of cotton in the plane of Tessenei.Ferdinando Martini (really admirable first governor of Eritrea, a stern anticolonialist and a refined man of letters) charged Mr. Coletta to study a project to irrigate the plane of Tessenei in 1905. During 1908, the Foreign Affairs Dept. charged Nobile and Avetrani to go on with this project, with the aim to counter the British growing of cotton in Kassala, Sudan, with the Eritrean production.Between 1907 and 1912 a group of North Italian manifacturers started a cotton production. But locusts and drought in 1913, and then World War 1 stopped the industrial manufacturing and for several years only some Italian agronomists grew cotton in little experimental fields.In 1924 the Khartoum agreement between Eritrean and Sudan governments unblocked the situation: the water of Gash river (named Mareb river in Hamasien) started to irrigate more than 37.000 acres in the plane of Tessenei,where, thanks to the new economic chances, families from different ethnic groups moved (Bilen, Maria, Atmariam, At Tacle, Baria, Kunama, Amhara, Takrur, Sudanese, Yemeni people). In 1926 the cotton reclaimed land was dedicated to the Crown Prince of the Italian Kingdom, Umberto.The variety chosen was Sakellaridis (or Sakel) cotton, of egyptian origin, long fibred, less productive than the american variety, but more valuable and desease-resistant; but in case of attacks of deseases, they were often devastating and hard to fight, at least with the old means.Women and children attended to the harvest; then, after the removal of the rejects (partly used to feed livestock, partly converted in oil for several, even alimentary, utilizations) the best fibres were pressed into bales for the european weaving factories.The “Guida d’Italia del Touring Club Italiano –Possedimenti e Colonie” already in 1929 named the Tessenei reclaimed land as the most important agricultural development success in the colonies.

Cotton fields near Tessenei

Near Tessenei, in Alighidir (sometimes named Aligider) was settled, after WW2, one of the most flourishing Italian firms: the Roberto Barattolo’s textile factory.Alighidir is still the land where the cotton for the manufacture ofscarves, futas and shammas produced in the workshop Alkemya, founded by Nadia Biasiolo, italo-asmarian, comes from.The Biasiolo family has been living in Eritrea for generations. The great-grandfather on Nadia father’s side, Hagop Seguliàn, came from Costantinople at the end of 19th century, escaping from the persecution of the Armenians, and he was already in Massawa when colonnello Tancredi Saletta, in 1885, landed in that port with the first Italian militar expedition. He became a supplier of goods for the Italian troops, and then he was a pioneer tobacco farmer.Nadia’s father, Giulio, an entrepreneur, had an eventful life, due to his closeness to the anti-Ethiopian guerrilla. He also founded in Asmara Afro Film, a film production company, that, between the end of the Sixties and the beginning of the Seventies, produced documentaries and also some internationally and well known appreciated movies, played in Eritrea: “Le mille e una notte” ( A Thousand and One Nights Arabian Nights) by Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Sette baschi rossi” (The Red Berets) by Mario Siciliano, “La via dei babbuini” (known in English-speaking countries as Highway of the Apes or Trail of the Baboons) by Luigi Magni and a TV serial for boys, “Verso l’avventura”.Nadia Biasiolo is now living downtown Asmara, and part of her house is a textile workshop.The idea was born in 1998, when a problem arose: to give a chance of working to lots of women, often widows of guerrilla fighters or they themselves ex-fighters during the Independence war against Ethiopia, not school-educated, but knowing, by family tradition, the ancient art of spinning. Having been a scholar of weaving at the Scuola d’Arte in Rome, Biasiolo thought of exploiting an art that in Italy is not practised since a long time, except, generally, in some hobbist courses. The number of the workers changes, depending on the periods; there have been even 28 workers in the workshop.

With their deft hands, the spinners pull a thin thread out of the soft cotton mass and roll it up on a reel; then the thread is wound in a hank by a skein winder.

The skein winder

A different thickness of the thread is typical of the hand working, and this of course marks the final product. The thread is woven on an ancient, simple two-healds loom, and beaten with an old reed. Some products are finished by crochet.

weaving looms