MV, Addis Ababa, April 30th, 2019

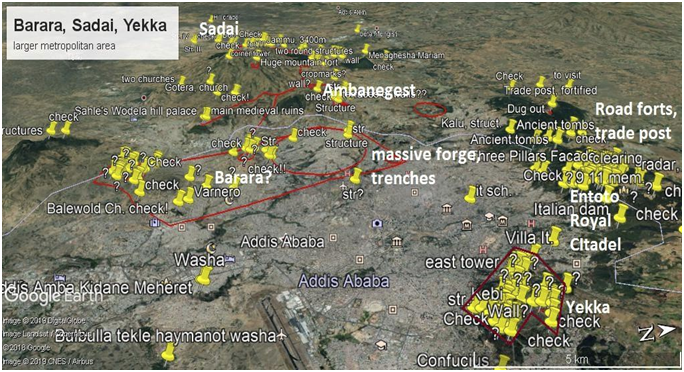

1 A quest for Barara produces dozens of unexpected sites of relevance

Two adjacent sites seen from satellite views last year and recently visited show a particularly high concentration of surface cultural materials. Enku Gabriel, “Saint Gabriel the precious” is the taller hill, Irti Mojo “the Mojo slope”, south of it, is richer in structures.

Considering that this area of central Shoa has been historically the fief of imperial power for a bout of around 150 years, from ca 1380 CE to the Muslim campaign of 1530 – the year Barara was utterly destroyed- ten to twenty pottery shards and obsidian cuttings per square metre indicate an urban, not a rural occupation. These, with the obsidian concentration in the area of Korke, not far, are the strongest cultural material densities in the whole area, one literally littered with medieval sites.

This, and some other considerations derived from the first visit, in April 2019, has prompted me to make a point on the present state of site research in the Addis Ababa area, and of the quest for Barara, the capital of Imperial Ethiopia in the mentioned late medieval1 period.

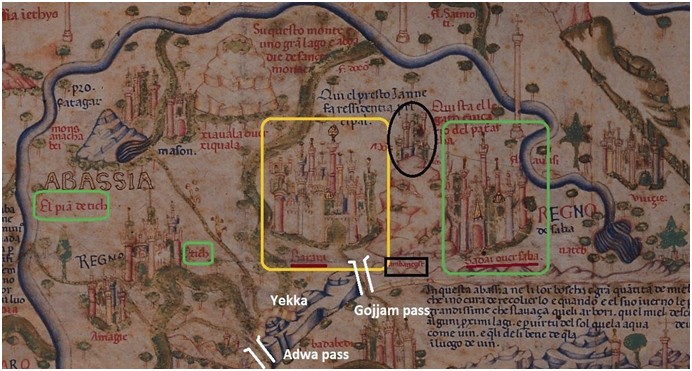

There is a map, in Venice, I have amply debated for its sixty five inscriptions and geographic names related to Ethiopia2. The hagiography of Ahmed bin Ibrahim al Ghazi, the conqueror of Abyssinia mentions Barara two times, and a Zarara four, likely they are the same main town3. Barara is mentioned in the majority of the 23 itineraries collected by OGS Crawford4, mainly on the escort of the itineraries compiled by Alessandro Zorzi. Once, with conviction, defined as a ‘metropolis’ by byssinian travelers, Barara necessarily formed the core of European Ethiopian connections then. In the mentioned century and a half, from 1380 to 1530 CE official missions alone from Abyssinia count to twenty two, versus two successful missions performed with evident difficulties by Europeans5,6.

Driven by his personal research on the might of the region around the age of the Mauro planisphere compilation (1450) Osbert Crawford, a global pioneer of aero-photography for heritage identification and management, spent time in Ethiopia in the fifties looking for Barara. Richard Pankhurst and his then young friend Endrias Eshete, two prominent scholars in Ethiopia, spent time strolling around Mt. Yerer in the same quest7, a bit later.

Hartwig Breternitz published the results of his two years quest for Barara, with Richard Pankhurst, in 20098. While Crawford concluded his exploration on the note that the ruins on Yerer are too limited to be a capital – I contend they are Masin, divided actually as on the Mauro map in two subsets- and Barara might have been on the Boror hill in Oromia – far too distant and deprived of ruins- Breternitz indicates different sets of ruins and classifies them, concluding Barara is probably somewhere under present day Addis Ababa. Addis is a megalopolis of ten millions and well above four hundred square kilometers. His is not a precise, nor a defining indication.

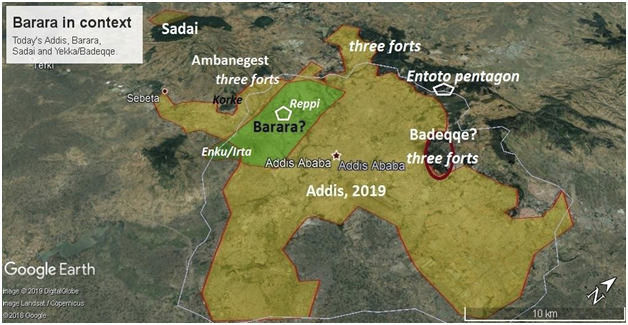

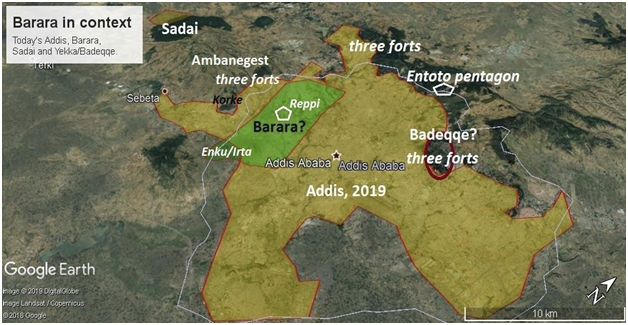

Since, ten years of satellite view research and site walking have identified, over and above those indicated by Breternitz and Pankhurst, forty sites with significant ruins, presumed medieval, some of which, the eleven forts in particular, though destroyed, are up to the highest defensive standards9. Two are of massive sizes, the Entoto Pentagon and the similar fort on Reppi, with external main walls enclosing respectively nearly one hectare and about one hectare and a half of strong structures10.

The extensive finds have in turn permitted a wide comprehension of all sites on the Mauro map, with the notable exception of Barara, the most significant site of the planisphere’s vast Ethiopia11 parts. New references have been confirmed, starting from the fact, already noted by Breternitz that the Doco river of the map is not river Dukem. I can assert Dukem is seen, without a name, with river Meki around Mt Yerer, indicated as Mons Anachabei, and Doco is the Akaki, clearly rising from the Entoto chain, near Yekka. Yekka hill is evident in a lighter colour, the highest crest of Entoto is depicted as a bluish rocky outcrop, and the identification of two passes, Gojjam and Adwa on the same chain is a diagnostic feature helping to identify a number of sites within and in the immediate vicinity of today’s ddis baba.

In my hypothesis too, recent construction in Addis has swallowed, rendered unrecognizable the structures and town tissue of Barara. For a part, it lied under the present continental Capital.

While the prominence the Abyssinian religious that designed all detail in the area for Mauro in 1439 CE gave to their metropolis makes it almost appear ante litteram as the continents’ capital, so far, in spite of fairly extensive, repeated searches, Barara remains unfound.

Matters have been, to me, complicated by illogic and rather Eurocentric inferences that since Axum Ethiopia would have had revolving camps, and no fixed capitals, apart from a spell in Lalibela, in the XII century, then a main camp in Tegulet, and a relatively fixed main town in Debre Berhan used only by Zer’a Yaqob around 1450. Tegulet actually stands today as a string of built sites of concrete stone constructions and a vast burnt Church or palace, Debre Work12. The Fra Mauro map, from a precise drawing of the area as it was around 1435 indicates expressly Barara as the Emperor’s main residence.

Eleven solid pre stellar, pre Shimbra Kure, pre 1530 forts, with at least thirteen coeval Churches found, and long ignored in Addis alone clearly indicate the presence of a major town, in fact, a capital, in the area.

2 Is Barara covered up, forever by a buzzing megalopolis?

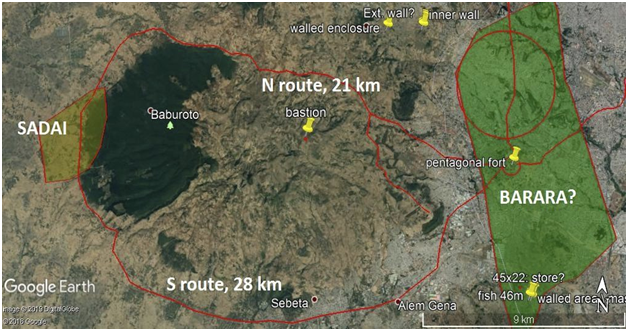

Bruce Strachan took note of a passage of the Fut’h al Habasha. The one in which the author mentions a six day distance between Debre Libanos and Barara. He took the matter seriously, as apart from it being one day march from hitherto unidentified Badeqqe, this is the only other distance reported from Barara to a known locality. He and friend Gelata marched from Debre Libanos, reaching the Gojjam pass on the sixth morning of a singular experimental archaeology feat. In effect Strachan had already noted vast ruins in Entoto, near that pass, ignored thus far by others13. He could have reached, in the course of the sixth day, the area from Kolfe to the South base of Mt. Wechacha, Mons Ajos on the Mauro map, where

it was designed by those Ethiopian monks for Mauro, a long area where I believe the “metropolis”, Barara actually lied. Part of its ruins can still be and definitely should be seen, excavated and studied, in peripheries not destroyed by recent vast condominiums sites. Before all sign of a splendid African capital is lost to all, forever.

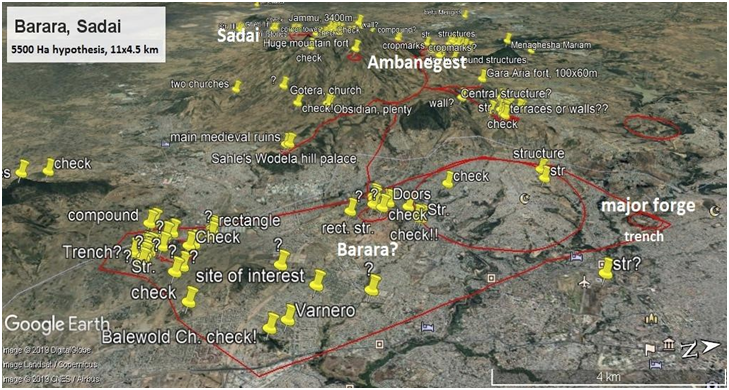

Mons Ajos, the Wechacha complex volcanic cone is topped on the map by Ambanegest, the “Fort of Kings”, a 2.3 kms of coarse walls still standing structure, a vast fortified flat top, comprising three sets of defenses and a bastion on its side14. This fortification covers over twenty hectares, nineteen and a half of main Amba, or fortified hill and 8,000 square metres of the facing trapezoidal fort. It is clearly the Ambanegest, fort of Kings recorded for Mauro by the visiting Ethiopian scholars, bound for Florence but necessarily transiting via Venice. Like Strachan, I first considered and published in a few papers the Entoto ruins, comprising a one hectare pentagonal fort and royal citadel, entrenched three times, with over five hundred metres of external ramparts and twelve towers, an elitist palace, at least thirty hectares of complex surrounding ruins. For a while, I thought Barara may have been here, as no one knew by then of such massive ruins in Addis Ababa, of clear ancient origin. This was before I turned my attention to the three forts, five villages and a vast rock hewn cathedral in the Yekka zone. Strachan holds a wordpress internet site on Washa Mikael, the twenty metre large, seven nave cathedral, another on Barara, a third on some of the most significant ruins around Mt. Yerer15.

I was trying to connect the Entoto site to the ancient Church indicated by Sahle Selase, in the diaries of visiting French missionaries, as standing below the large tree long known as Birbirrssaa, where the terminal metro station now is, and Minilik’s equestrian monument next to St. George. So for a couple of years I believed and stated the capital must have been between today’s Piazza and Minilik’s Entoto. I managed to completely differentiate Minilik’s camp, with its main ‘red tent’ from the Royal citadel and, muck like the Shoan king that reunited and much enlarged Ethiopia, associated it with Dawit II, or Lebna

Dengel, around 1515. But soon realized this was an elitist site not only above, but at a certain distance from Barara, the Capital.

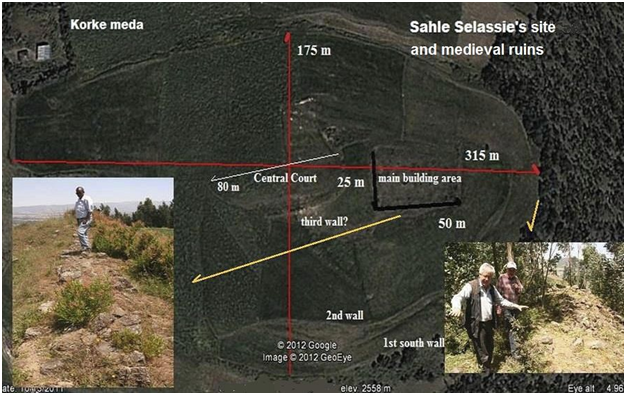

This because visits to the Korke field, not far from Sahle Selase and Minilik’s local camps, the old Entoto and likely the ntutna of the Futu’h campaign log, revealed masses of cultural materials and the site of a massive Church, covered in 1830 by Sahle, king of Shoa with a 30,000 ton capable granary, equivalent of the biggest storage facilities possessed by the Prussian Kaisers at the time. My attention turned to the slopes of Wechacha. A friend and former student, topographer Abel Gebre Yohannis had shown me the new road he had designed crossing the Entoto chain in Yekka, through the Adwa pass of Minilik’s time,

clearly shown on the Mauro planisphere. Since, the distance from the two helped me on the quest for more towns on the map, and, critically, convinced me Barara could not be so near the Gojjam pass, or today’s Piazza.

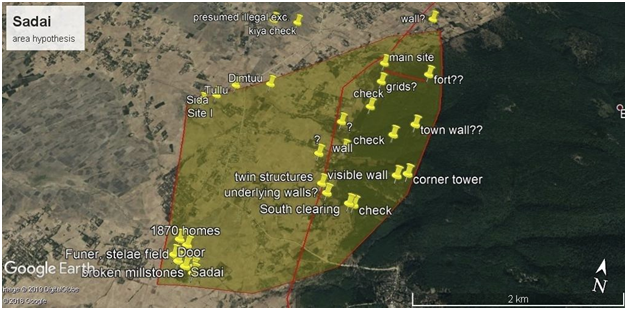

3 The capital of ‘Abassia’. What to expect

Sadai is indicated on the map as Barara’s twin city, the other side of Mt. jos or Wechacha, well entrenched into its western slopes. In 2014 I started seeing bits of it, sparsed in an area at least eight hundred hectares wide, some four kilometers by over two by axes. US archaeologist Sam Walker immediately did, under my eyes once at Addis Ababa University, a thing I had thought of not much use, he went back in time using the ‘clock’ on googleearth to reveal earlier satellite photography. I thought the trees in the area were original and may have dated from the park, the first national park globally, dating back to 1435. They were instead a recent plantation of eucalyptuses, not older than 2003, so, inside the park, at the base of Wechacha, appeared three sets of major ruins in a four kilometers long line. Successive visits confirmed the elitist, rock structures of Sadai were inside the park, as Walker affirmed and published.

A vaster area, less rich in construction but comprising most likely popular housing, in organic matters like earth daubs and straws, wood palisades and some significant likely preexisting Oromo sites extended to the west, where I had seen sparse ruins.

We should expect Barara to be similar in build: a set of elitist hill tops and palaces, rock based structures somewhat distanced, like Parishes, each with its Church. Rases and military figures, negadrases and bitweded, members of the local bourgeoisie and nobility holding the safer, better grounds, surrounded by huts of organic materials, palisades, connecting paths and roads. Do not expect anything like the moving camps Minilik held, and a long historiography has indicated. They existed, as a vast Empire imposes, but not where Emperors built long standing, extremely well defended permanent capitals lake Barara. On the other hand, small, trodden cultural material and pilfered walls, are easy to overlook and are soon utterly destroyed, if sited in a built area.

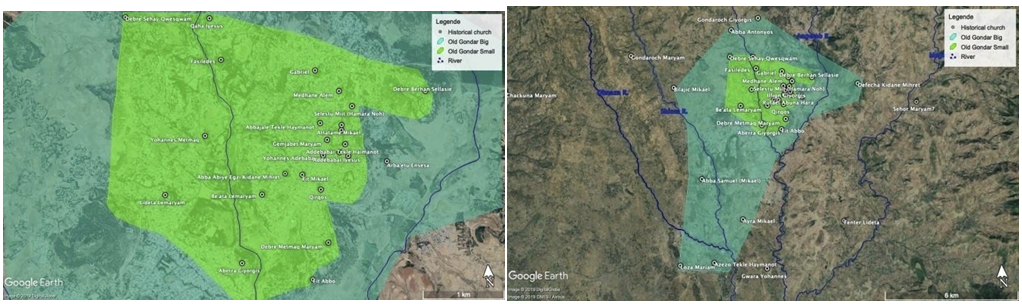

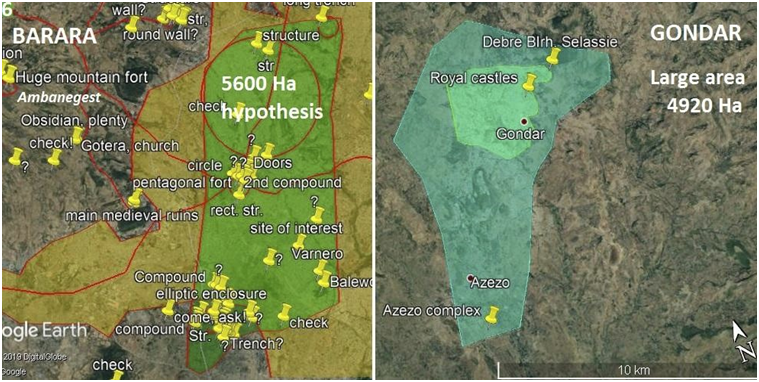

I find particular value in a comparison with later, likely less flamboyant and certainly less rich Gondar, considering the massive trade worth and land losses incurred after the 1529 massive Imperial defeat of Shimbra Kure, near mount Yerer. Barara must have been wider, richer, possibly better built, even. Gondar still stands divided into parishes. Family compounds were large, as much as one thousand square metres each. Scholar Andreu Martinez d’ los Moner has summed historic Gondar for me in two hypotheses, exactly basing himself on core and more peripheric Churches.

Gondar, much like Harar as seen in the Robecchi Brichetti XIX century photos, had solid rock buildings, but much, evidently soon lost organic daub huts, straw tall roofs, wooden palisades. Elitist and popular went together, not far above water streams, in defensible areas where the rulers held higher ground, dominating trade routes, and agricultural plains.

A wider Gondar, as indicated to me by Doctor Martinez, corresponds largely to the area I indicate as worthy of inspection today, as likely constituting ancient Barara.

4 Here lied Barara. Arguments for an hypothesis

4.1 The strongholds.

Eleven fortifications surround an area of north western Addis Ababa. One more than later, splendid and showily rich Genoa “La Superba”, in the XVII century.

They are divided in three groups, and two single forts. A first group, starting from East, appears definitely as a separate major Imperial site altogether, while functioning as a strong access from the East, where the most dangerous enemy proved to be. I have indicated the three forts, one military citadel, at least four villages and Washa Mikael cathedral probably constituted Badeqqe, as mentioned, one day or less than twenty kilometers march from Barara.

A second, also of three forts protects the roads to Amhara, or, in the local contemporary context, may rather have protected the incumbent from Amhara, family plots and armies proceeding from the North.

A third group closes Barara from the West, letting vital communication with Sadai, a trade and Episcopal town filter through16.

The single forts, the most monumental, appear as strong pentagons in Entoto and Reppi hill.

Trade routes and agricultural bounty justify Barara and its ecological and social context.

Barara in context, fort groups, emplacements within Addis Ababa today

4.2 Trade routes

Sadai was Barara’s door to the West, where Ivory, Medicine, Zibet musk, Slaves and Gold mostly came from. The routes connecting the two were likely via the western set of forts, for two simple reasons: the presence of the forts themselves, and the reduced distances of a North route, North of Wechacha avoiding the climb and dense forest that covered the southern slopes.

I have dedicated a paper to the three forts found recently in the Gulele botanical gardens. One, Ona Meda appears distinctly as a post for horses, or a fortified point controlling trade. A much vaster structure still under recognition above Sululta, thirty hectares wide, may appear as an ancient trade caravanserai recently modified for military exercise purposes. Fiche hill, a terraced height below, on the ancient route directly connecting Amhara and the area I recognize as Barara shows a dense bounty of cultural material scattered on its sides, of hitherto unseen and often decorated sorts.

Koye hill in extreme SW Addis Ababa has a fort, number twelve in today’s Addis Ababa, I have not published yet.

Francis Anfray is the sole academician to have conducted site visits and excavations in central Shoa and within the area I consider here, apart from an extemporary but complete study of Ghimbi Tewodros by Ricci and Fattovich, dating back to 1973, and of Monneret the Villard and Sauter’s older notes on Washa Mikael in Yekka. He published his excavations of a tower in Insilale Tiko, on the route South and Southeast of Barara. This trade route passes via Sire, as published by Breternitz and Pankhurst and finds first a set of sites noted by Crawford, I see clearly indicated as Masin below mount Yerer, on the Fra

Mauro planisphere17.

4.3 Bountiful land conquered and held

I have argued a 15.000 hectares land stretch alone, of what the original design by the Abyssinian monks described to Mauro as a vital plain, “el pia’ de tich” near Tich or Tilq, Zer’a Yaqob place of birth, I identify on a bend of river Akaki, as on the map, South and East of today’s Bole airport up to mount Yerer, would have produced some 120,000 quintals per year of teff, wheat and barley confused, equivalent to enough 2000 Kcal per day ratios to feed 65.000 persons for a year.

Lands in the area are FAO class eight and nine, amongst the most fertile anywhere.

I claim to have located Vuicie in 2015. It had similar vast plains, possibly just one notch lower in fertility.

These are just, very indicatively, below one fifth of potential cultivated land around Sadai and Barara.

The Tilq plain and Vuicie would have fed over 100,000 people, the wider Sadai/Barara area of central Shoa could have sustained half a million18. This is a wealth and a fundamental resource that certainly conditioned the capital’s choice of emplacement, as much as the presence of trade routes and a distinct rim of protective mountains, from the Entoto chain with the two passes I mentioned, wide Wechacha, Furi and Yerer closing the fertile shell.

Barara and Sadai combined could easily have reached a total population approaching perhaps 150,000 individuals, including peripheries. Gondar had eight thousand homes, or at least 70,000 inhabitants according to James Bruce. Barara and Sadai had, within a couple of generations, deprived most of Mount Ajos, or Wechacha of its cover, for building but mainly for fuel wood, cooking uses. Here lies the ecological reason for the creation of the Menaghesha Suba Crown Forest, ca 1435. A logic, necessary and far fledged decision by Zer’a Yaqob. Well over a century before what most consider so far as history’s first National Park, the Bodgkan Uul mountain, above similarly overpopulated Ulaan Baatar of the then extremely powerful and rich Mongols19

4.4 A forge, a fort and long trenches. What ddis baba’s growth has left us

A large medieval forge was identified in Kolfe years ago. The find was never published, nor understood in this context. Massive sludge and many tools were recuperated20.

The Reppi pentagonal fort, at a staggering 1.4 hectares covered by main external towered walls is the vastest in Addis Ababa. We could not approach it as it is a military restricted area and the siege of a State radio station. One of its semicircular towers appears to have been reconstructed, or perfectly preserved, seen from a distance. We could not find any notable cultural material on the ground.

An area of Kolfe, at the extreme North of the study area I propose is surrounded by deep trenches, apparently ancient. It is a police academy now, again we could not visit it.

Above town, in the Wechacha Mariam area and in the Korke plain, also a very significant, seven hundred hectares wide agricultural production zone, the Wedela hill fort is a large fortified area. Sahle Selase’s and Minilik’s camps stood atop the ancient fortifications, this is as mentioned the old Entoto. It took less than two weeks, some ten days according to Jules Borelli, to move tents and woods from the Minilik really movable camp to the new Entoto, when he claimed he had found Dawit’s

fortified town, or Ketema.

Raising the hundred thousand big stones forming the defenses of the underlying ancient fort would have simply been impossible, and senseless.

4.5 A long mountain side, the Barara hypothesis summarized

I presume Barara lied from Kolfe to its North to Irti Mojo to its South, let it comprise or not the higher Korke plain to the West and the hills around the Balewold Church to the East, one of which, likely Balewold hill itself, had the “heads of a Church’s columns” -much more likely their bases actually- come out of the soil, at a visit by French explorer Theophile Lefevre around 1854. There may have been a central or core area, well under long built western quarters of Addis Ababa, as in Dr. Andreu Martinez’s smaller area, core historic Gondar hypothesis. Ruins hard to detect if in a modern urbanized area, I insist, considering the way the Enku Gabriel main structure’s external defense wall has been picked in large tracts, stone by stone, only leaving leveled, yet wide foundations, still visible from satellites.

Elitist high ground, defendable resident areas would have been central to parish like quarters. Most of town would have had a rather dispersed structure otherwise, I mean, a somewhat dispersed texture not so different from the much less dense Addis of Minilik’s age, soon after its re-foundation as a capital, around 1900. Then every nobleman had his “sefer” or camp, as Etegue Taitu, the Empress had put it, to let rival esquires develop town instead of factious skirmishes and dangerous hostile designs of alliances and a possible attack at her consort’s primature.

5 A South Barara parish, sefer? A first visit to two new sites

The two adjacent sites are characterized, from satellite views by two hill sides, the first, Enku Gabriel, taller and with two rounded lowly tops, the second, less accentuated, showing more prominent ruins.

Enku Gabriel was until its foundation, by just a handful of families or less than thirty people, thirty years ago, an area of sparse Oromo rural occupation. New residents are totally unaware of both the extensive ruins and of the diffused, but fragmented cultural material. No informant knows or guesses a previous occupation. A southern hilltop, near the one occupied by the recent church, lies a six thousand square metre wide enclosure I had named the “paper clip” from its shape, at discovery last year.

As mentioned in my introduction, it is the density of cultural material, obsidian and pottery shard in primis that shows the area has been if relatively briefly, well inhabited, at urban, not rural levels of occupation. We met it all over the “paper clip” and areas South of it, and on the second hill.

An enclosure, about two thousand square metres in size lies near the top of Irti Mojo. It appears to have been modified by a local resident family on the West side. I cannot judge the age of its external walls. A local resident, Biniam, attributes them to an unspecified Imperial period. The five thousand residents have settled recently, the only Church in the area, Enku Gabriel, is one generation old. None of the met residents knows a dating or attaches any signification to the ruins in the area.

Just North of the enclosure is a definitely old structure, 45 x 22 metres wide, with three rooms annexed, one of which is a round external tower, over 4 metres in diameter. A bit further, a forty six m long and thirty five wide compound, likely rich, elitist, with developed inner structures. I had dubbed it the fish, for its appearances from sat views.

Cemeteries in both sites are singular, built in large stones, well weathered, appear totally alien to local, recently settled communities. They are definitely worth excavating.

A terraced hill slope in Irti Mojo has ancient cemeteries, again unknown as to their origins to resident informants and a set of walls on top.

6 Conclusions

Ethiopia is living a period of great hopes, recovering from a spell many would define as the rapid fall of a regime dubbed as a cleptocracy, riddled with corrupted leaders.

Times are still unstable, after some violence and further menace of violent actions helped foster the regime change, while debt and a hitherto unknown level of local disturbances, criminality and police order disruption, partial economic stagnation announce times of relative insecurity.

Yet, discovering that within the continental capital, Addis Ababa is not just yet another piece of the recently appreciated historical reconstruction of medieval African might -so far a matter for academics and the most forward looking historians, archaeologists and other specialists- but perhaps this capital may be the biggest bit of it all, with unrivalled structures and population densities, stable capitals and clear signs of power, wars, trade wealth not second to any other contemporary world nation is a feat that cannot be underestimated.

My recent pledge to scholars, archaeologists in particular still waits for action and local and international answers. I am sending it personally to more academics.

There is not, never enough underlining, as I have insistently proposed in the last few years that the sites of the ‘Preste’, much more than those of the rival Sultanates are being destroyed continuously.

The hills of Irti Mojo and Inku Gabriel, from forgotten backwaters on depopulated slopes of Mt. Furi are now dangerously near the new Djibouti railway station. In months, local residents have surged in Irti Mojo alone to around five thousands, from about three thousands.

The last victims, in the last months of various developments and simply of peasants in search of land near and within what is clearly the densest and most rapidly growing area in the Horn, megalopolis Addis Ababa are the Entoto Pentagon (sic!) hit by tall trees fell by the local police family, with the loss of a tower top, and Sire, hit in its core by a peasant that has built all over it, using the well cut stones that formed its walls.

Raise and realize there is no replenished future without understanding our brilliant past.

Preserving it is worth hundreds of millions21. Not fighting for it is a shame unworthy of those now in power, a mistake Ethiopian Pride will correct, I do hope, in time. That is, now.

MV, Addis Ababa, April 30th, 2019

Notes

1. The middle ages have for long been interpreted in general historiography -that is basically in diffused Eurocentric sources- as a period of decline after the “fall of Rome” and before the European renaissance. Recently high end, cultivated reads and videos have cleared to attentive and learned minds Arabs of African origins brought back to Europe in El Andalus and selected

universities the Greek culture they had preserved and enriched. There was no such thing as an abrupt ‘fall of Rome’, as Diocletian in 215 CE had founded Nova Roma, today’s Istanbul to cope with a significant and ever growing trade with the Orient, managed mainly via the safer, better oceanic routes, where Axum was the West’s best, most durable ally. The period after 456 CE was at first absolutely splendid in Ethiopia. After a slow decline tied to the loss of ports to Persia, while the Zagwe dynasty held the port of Zeila and was no prayer dedicated enclosed society alone, but based its wealth and amazing construction feats on trade, came the age of Barara. Followed by a later less splendid period, that of Gondar (XVII to mid XVIII centuries). Africa was the richest continent in the age of Barara, there was no middle age decline in Ethiopia. That happened rather in the XVIII and early XIX century, during the divisive ‘age of princes’. Ethiopisants consider Atze Tewodros reign and modernization push as the end of middle ages in Ethiopia, in the core of the XIX century.

2. Vigano, M., 2016, The Fra Mauro Code, academia.edu, San Francisco. A full list of inscriptions transcribed by Piero Falchetta are online. Cfr. also: Falchetta, P. Fra Mauro’s World Map: A [new] History, http://www.academia.edu/9720850/Fra_Mauros_World_Map_A_new_History

3. Futu’h al Habesha on Barara and Zarara: cfr. note 9, page 26 on my ‘The Missing Tower at the Entoto Royal Citadel’, Academia.edu, 2015. Sihab ad-Din Ahmad bin Abd al-Qader bin Salem bin Utman, The Conquest of Abyssinia (Futuh Al-Habasa), Cesare Nerazzini translation, La Conquista mussulmana dell’Etiopia nel secolo XVI, Roma, Forzani e C.,1891.

4. Crawford, O.G.S., ed., Ethiopian Itineraries ca. 1400-1524, including those collected by Alessandro Zorzi at Venice in the years 1519-24, Cambridge Univ. Press/Haklyut Society, 195 p.

5. Krebs, Verena. Windows onto the world: Culture Contacts and Western Christian Art, 1400- 1550. Abstract on Academia.edu.

6. Salvadori, Matteo, 2018, The African Prester John. I have had no access yet to Salvadori’s text, only received comments on it by some of my followers online.

7. Richard Pankhurst, personal communication

8. Breternitz, Hartwig and Pankhurst, Richard, Barara, the royal city of 15th and early 16th century (Ethiopia): medieval and other early settlements between Wechecha Range and Mt Yerer: results from a recent survey, Annales d’Ethiopie,Volume 24. p. 209-249, 2009.

9. Vigano, M., 2018 Ten forts in Addis and six in Hararge: of advanced military might, on the emplacement of Barara, capital, academia.edu, San Francisco

10. Vigano, M., 2015, The Missing Tower at the Entoto Royal Citadel, academia.edu, San Francisco; Sadai stelae town.. etc, also on my academia page.

11. Ethiopia covers over a third of Africa on the map. The name Ethiopia, or land of the dark skinned, was in the whole east third of Africa an equivalent to the Arab Bilal es Sudan, a general term for Black Africa. This rendering has been prepared by Piero Falchetta, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, the map owner. I added parts to the left up, on the ‘Diab isle’, as they are indicated by the mapmakers, the mentioned Ethiopian religious, as recently occupied by Zer’a Yaqob. The channel, ‘Cavo de Diab’ is to me thus no sea channel, but the rift valley lake system. Diab, cfr. Dehab, Arab for gold is related with the gold rich Monomotapa and Swahili areas, not to Madagascar as generally believed so far. See Vigano, M., The Mauro Code, ibidem. I am

indebted to Sam walker, here. He first made this observation.

12. Tegulet was re-discovered in 2017 by Walker, archaeologist, and author. Cfr. Walker, S. in Popular Archaeology and Vigano, M., academia.edu

13. See Strachan’s dedicated blog, barara.wordpress.com. I drew paths from Yekka (Badeqqe?) and from Debre Libanos to the core of my Barara hypothesis area on google earth. I obtained 16.5 and 99km respectively. A proportion of one to six. It is reasonable that the walking distance, particularly if loaded with ‘arma et impedimenta’, weapons and baggage, as military troops would inevitably be is respectively one and six days, as indicated in the Fut’h al Habasha.

14. Ambanegest appears in a number of papers in the Medieval Ethiopia Recovered section of author’s academia.edu page: http://addisababa.academia.edu/MarcoVigano. Here is a satellite view of its massive fortifications. Successive openings in the three successive lines of defense all point to the bastion low left in the view. Its occupant family conducted͙ extensive excavations!

15. Bruce Strachan also manages the sites gimbi.wordpress.com and washamikael.wordpress.com

16. Wechacha forts include Ambanegest, cfr. note 14 above, the Wedela hill fort, see page ten (10) here above and the Gara ria rectangular fort. See Ten Forts in ddis͙ ibidem.

17. A few of my earlier papers position Masin, as the map clearly shows, under Mt. Yerer, cfr. e.g. Vigano, M., 2013, The Names Lost, The map grasped, academia.edu, San Francisco.

18. A first evaluation of human population carrying capacities in the area was attempted in my https://www.academia.edu/26052539/The_shapes_of_medieval_Addis_Ababa, on p. 15. See also:“Vuicie? border rural hamlet in medieval Abassia, ca 1430”, p14. I took an area of ten by five kilometers in the mentioned ‘pia’ de Tich’ or Tilq, Tich’s plain under Mt. Yerer, valuated an average yield of teff, 4 qls per Ha and over ten of wheat and barley, an average of 8 qls per 15,000 Ha. I thus obtained yearly crops for 120,000 qls, at 4Kcal per gram, sufficient 2,000KCal daily ratios to feed 65,000 for 365 days. The Tilq plain is a minimal fraction of the arable land in the Barara and Sadai ecological area. This photo, from an area of the Tich plain, shows the proposed Barara area, under Mt. Wechacha.

19. Vigano, M., 2016, Sadai stelae Town, etc., ibidem

20. Dr. Kasaye Bagashew, AAU, Abel Assefa, ARCCH, personal communications

21. I conservatively valuated the worth of the two National parks in and near Addis, with the included and non included medieval sites I recovered and described at 270 Mio USD, on the basis of two extra days spent in Addis by a fraction of visitors. See Ten forts in Addis and Six in Hararge.. pag. 16. A rapid calculation on the hypothesis that ten per cent of tourists may visit the sites is reported here: “900,000 x 0.10 x 2 days x 150USD = 27 Mio USD yearly; V = 27/0.10 = 270 Million USD (V: total value). This is the calculation I presented to my students in the second board͙”. The .10 or 10% divider allows the transformation of yearly revenues to a permanent value. It was valuated, necessarily on a conservative basis, on the escort of returns of cultural investments in Italy over a long period of time.